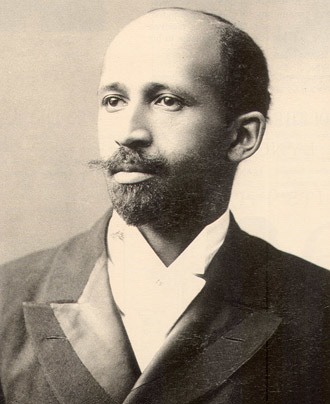

William Edward Burghardt “W.E.B.” DuBois once said, “A classic is a book that doesn’t have to be written again”. Although he may not be the first figure that comes to mind as a classic author who has contributed to the American literary canon, DuBois was not only a renowned scholar who generated waves in the movement for racial equality—he was also a prolific writer.

Du Bois published an astounding nineteen books, many of which are classics. He also edited four magazines, coedited a magazine for children, and produced a number of articles and speeches during his lengthy career as an activist, Pan-Africanist, sociologist, educator, and historian.

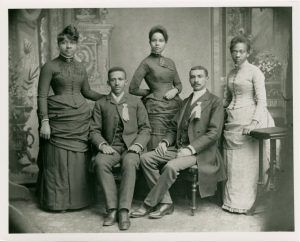

Class at Fisk University

DuBois lived from 1868-1963; he was born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts and died in Ghana. An extensive family network helped raised young DuBois, who then went on to receive an elite education. He studied at Fisk University in Tennessee and subsequently Harvard University and the University of Berlin. DuBois’ education, quite different from his upbringing in a mostly European American town where he freely attended school with Whites, exposed him to issues of racial prejudice and the brutal reality that the Jim Crow laws enforced for African-Americans at the time.

As the first African-American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard, DuBois would develop into arguably the most influential African-American thought leaders of the 20th century. He later taught as a professor at both Atlanta University and Wilberforce University. One of his most notable accomplishments is his position as co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) where he edited a newspaper called the Crisis—many of his essays from this time were published in book form.

The Souls of Black Folk

DuBois’ landmark study titled The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study (1899), the first case study of an African-American community, marked the beginning of his writing career. His most famous classic, The Souls of Black Folk (1903), was prompted by the disenfranchisement of the African-American community, and in particular, the lynching of Sam Hose in 1899.

The Souls of Black Folk is a poignant collection of 14 essays through which DuBois defines critical components of the African-American experience. He introduces terms such as the color line, the veil, and double consciousness; the latter of which he coined as depicting the fragmented identity of the African-American who must reconcile the perspective of themself with that of White America, which thus damages and ultimately shapes the African-American’s sense of self. Although the classic initially met a negative reception, it is now warmly embraced as a cornerstone of African-American literature.

Double Consciousness

I’ve recently had the privilege to read other works of DuBois that are frequently overlooked, but nonetheless, speak to his capability to write and write well in all different types of genres. Take for example, his science fiction short story titled The Comet (1920), which situates a Black man and wealthy White woman in New York City in the wake of toxic gases that have proved fatal to the rest of humanity—here DuBois attempts to theorize a present in which the historical oppression of the past may no longer represent a marker of inequity. His range is also demonstrated by his biographical account, John Brown (1909), which masterfully pieces together records and documents to recount the life and legacy of the White abolitionist and the raid on Harper’s Ferry.

DuBois was working on the Encyclopedia Africana, which includes information on Africans and peoples of African descent throughout the world, when he died. He will forever remain a talented and groundbreaking literary figure in American history—his multitude of publications, most certainly make sure of that.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.