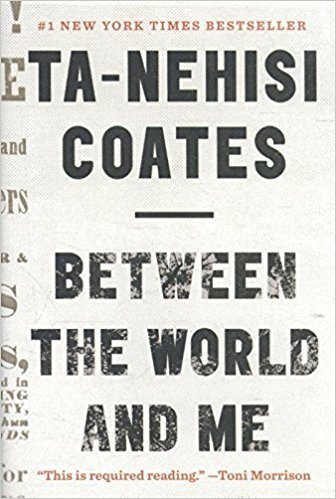

Toni Morrison dubbed Ta-Nehisi Coates’s memoir, Between the World and Me, “required reading,” and, from the very first line, I understood why. Coates’s writing is powerful, expressive, and angry. This last quality was what I found most jarring, and most rewarding, about his piece. Unlike many other writers who dance around issues of race, Coates is angry and he allows himself to be.

Coates doesn’t make any excuses for the rage that permeates every word, and he knows he shouldn’t have to. It’s refreshing, frankly, to hear him place the officer who murdered his friend, Prince Jones, on the same level as the terrorists behind 9/11. Yes, it’s disorienting; as I read the passage, my eyes widened at his boldness. But by the end of the book, I realized that it wasn’t his boldness that shocked me. It was his honesty. Over the course of his life, Coates has experienced the issues that I’ve only read about in newspapers. Of course he’s furious. Of course he’s livid. To him, this is personal—a violence that constantly threatens him and almost everyone he loves. Of course he’s angry. How can we expect him to feel anything else? Why do we expect him to feel anything else?

Coates frames the book as a letter to his son, an expanded version of the type of “talk” that most Black people have with their children, the sort of conversation that may be foreign to those fortunate enough to never think about it. The physicality of Black bodies and the violence inflicted against them, the way Western education fails the Black community, and the corruption of the American Dream—these are all poignant themes throughout the book, and serve dual didactic and expressive roles. Coates establishes the most important of these themes from the start, beginning his book with these weighty words: “Son: Last Sunday the host of a popular news show asked me what it meant to lose my body.” This line, so seemingly mundane, so huge in its smallness, conveys the central image stamped on every page of the book: losing your body. Defending your body, healing your body, having your body taken away, having your body broken. Coates assumes this corporeal relationship as fundamental to the Black experience, and this shocked me—and enlightened me.

There are many forms of racism we must confront in the U.S; some of it stems from federal issues, such as many of the problems that recent immigrants face, while some of it is more subtle, such as the microaggressions that plague almost anyone who is not a cisgender, heterosexual white male. However, the manifestation of racism that Coates describes is surely the most deep-seated, the most far-reaching. It targets the Black body. It’s brutally physical, violently personal. It affects people in the most primitive way, appeals to base instincts and yields the horrific results we superficially mourn in the news. Coates addresses this: Freddie Gray, Tamir Rice, Michael Brown—these people were not solely killed by individuals, by police officers, or by white men. They had their bodies taken from them in the most primitive sense of the word; they had their bodies taken from them by the system of ingrained racism so pervasive in America that it is now virtually invisible to all but those affected by it.

There is no way to analyze or dissect this horror. It has no rationality. It is an age-old beast that reveals itself selectively, hiding in plain sight until it strikes. Until we are more aware of it, the burden of combating it falls to those most vulnerable to its attacks. In Coates’s haunting words to his son: “You are a black boy, and you must be responsible for your body in a way that other boys cannot know. Indeed, you must be responsible for the worst actions of other black bodies, which, somehow, will always be assigned to you. And you must be responsible for the bodies of the powerful—the policeman who cracks you with a nightstick will quickly find his excuse in your furtive movements. And this is not reducible to just you—the women around you must be responsible for their bodies in a way you will never. You have to make your peace with the chaos, but you cannot lie. You cannot forget how much they took from us, and how they transfigured our very bodies into sugar, tobacco, cotton, and gold.“ (Between the World and Me, 71).

Read Between the World and Me here.

About the Author: Ta-Nehisi Coates

Ta-Nehisi Coates is an American author, journalist, comic book writer, and educator. Coates is a national correspondent for The Atlantic, where he writes about cultural, social, and political issues. He has contributed to The New York Times Magazine, The Washington Post, The Washington Monthly, and other publications. In 2008, he published a memoir, The Beautiful Struggle: A Father, Two Sons, and an Unlikely Road to Manhood. His second book, Between the World and Me, was released in July 2015, and won the 2015 National Book Award for Nonfiction, and was nominated for the Phi Beta Kappa 2016 Book Awards.

Coates is a 2015 recipient of a MacArthur Genius Grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.