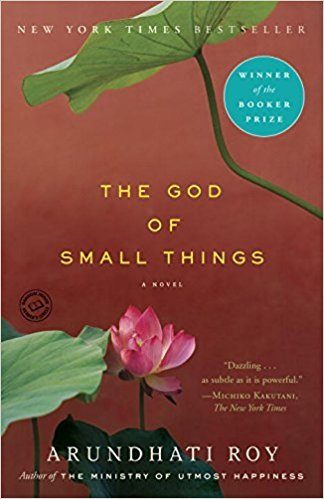

In light of the long-anticipated release of Arundhati Roy’s second novel, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, what better time to look back on her stunning debut, The God of Small Things? Winner of the 1997 Booker Prize,

Winner of the 1997 Booker Prize, The God of Small Things was an instant, immense, and international success. After its publication, Roy deliberately distanced herself from fiction writing, turning her attention instead to political activism, in reaction to rising social conflict in India.

Finally, after twenty long years and a book over ten years in the making, she has once again decided to grace the fiction world with her genius. To better understand her writing and her evolution as an artist, let’s rediscover the gem that is The God of Small Things.

“May in Ayemenem is a hot, brooding month,” the novel opens. “The days are long and humid. The river shrinks and black crows gorge on bright mangoes in still, dustgreen trees. Red bananas ripen. Jackfruits burst. Dissolute bluebottles hum vacuously in the fruity air. Then they stun themselves against clear windowpanes and die, fatly baffled in the sun.”

There is a haunting, surreal beauty in Roy’s writing. Instantly, we are transported to a different place and time: 1970s Ayemenem, a small town in Kerala, India. Roy’s command over English illuminates the novel; a raw musicality inflects every line of her narrative. In addition to this striking lyricism, Roy also embraces unconventional rhetorical techniques: capitalization, compound words (such as “dustgreen” in the passage above), neologisms, and sometimes all three at the same time (“Furrywhirring and a Sariflapping,” on page 4). “A novel of real ambition must invent its own language,” John Updike wrote of The God of Small Things, “and this one does.”

As far as plot goes (in light of the sheer power of Roy’s writing, it’s almost easy to forget about plot), The God of Small Things attains both specificity and universality. It explores the tumultuous lives of a well-off Malayalee family, but dissects broader themes of love, identity, trauma, and belonging. The novel’s protagonists, Rahel and Estha Ipe, are “two-egg twins” who share memories and a tragic backstory: when they were seven years old, their mother (“Ammu”) conducted a clandestine affair with Velutha, an Untouchable. After the scandal was uncovered, the Ayemenem microcosm spiraled into chaos. Velutha was murdered, Ammu was ostracized, and the ensuing escalation of catastrophes resulted in the death of Sophie Mol, Ammu’s brother’s beloved child. Roy’s narrative, focalized on Rahel, harnesses a nonlinear timeline to poignantly illustrate the degree to which the twins’ childhood trauma defines their lives. Roy unflinchingly demonstrates the ways in which the twins’ relationship with time is warped; they are ensnared by the past, endlessly circling back to it to relive, reconstruct, and deconstruct the trauma of their childhoods.

To fully understand this regionally-specific plot, it’s important to grasp that The God of Small Things isn’t just a family drama; it’s also—some might argue primarily—a sociopolitical commentary. In postcolonial India, the caste system placed a rigid hierarchy on human life. Much like slavery in the western hemisphere, the caste system deemed some superior and some “Untouchable.” Although the Ipe family is Syrian Christian, a demographic that does not adhere to the caste system, they are by no means immune to its far-reaching, deep-seated influence throughout the peninsula. Therefore, when Ammu—an upper-class woman from a Syrian Christian background—engages in an illicit romance with Velutha, an Untouchable, the consequences are unimaginable.

As Roy explicitly points out, it would be easy, but lazy, to say that the events of the novel came about because of the caste system; in reality, the story “began long before Christianity arrived in a boat and seeped into Kerala like tea from a teabag. That it really began in the days when the Love Laws were made. The laws that lay down who should be loved, and how. And how much.” In The God of Small Things, these Love Laws are broken one by one, sometimes quietly, sometimes explosively: interracial love, inter-caste love, and, finally, in one shocking but—in retrospect—seemingly inevitable passage, incest.

We can’t talk about The God of Small Things without talking about the incest between Estha and Rahel that shocked the world, causing the book to be banned and burned even as it was adored by critics internationally. However, much of the criticism misrepresents the incest as vulgar—salacious, almost. Roy blatantly contradicts this reading, writing that what the siblings “shared that night was not happiness, but hideous grief.” As the novel unfurls, it becomes starkly clear that the twins’ shared trauma renders them two halves of a broken whole: the “Emptiness” in Rahel’s eyes finds a natural counterpart in Estha’s “Quietness”—he has not spoken in years. The trauma of his past settled deep within him, morphing into a monster that “stripped his thoughts of the words that described them and left them pared and naked. Unspeakable. Numb.” Both twins are trapped, shrouded in the deep, bleak past.

Larry McCaslin, Rahel’s ex-husband, became “offended by her eyes,” by their emptiness, but what the ill-fated man could never understand about Rahel’s inner world was that he was only seeing half of it—that “the Emptiness in one twin was only a version of the Quietness in the other. That the two things fitted together… Like familiar lovers’ bodies.” It follows, then, that the two cleave to each other, when no one else can fathom the depth of their trauma. That the communion they share—in the form of common memories and common tragedies—would syllogistically lead to the breaking of the last Love Law.

Roy leaves it to us to judge the validity of these so-called Love Laws. She calls to our attention, however, their inherently arbitrary, discriminatory nature: while we may scoff at what we perceive to be an overreaction to inter-caste romance (“What’s the big deal?” many Western readers asked. “They’re all Indian, right?”), she gently but firmly presents us with incest—an unspeakable taboo everywhere, right? Wrong. In some parts of the word, incest is accepted and encouraged. So what, then, are these Love Laws? Who decided upon them? Who is to say which are right and wrong? Who has the right to love who? And how? And how much? In forcing us to ask ourselves these questions, Roy urges us to look inward—to examine our own biases, our own “Love Laws,” and reflect on why we think the way we do.

Yes, The God of Small Things is, as its title suggests, a novel about the small things: A family torn apart. A girl buried in “a special child-sized coffin.” Two siblings who “thought of themselves together as Me, and separately, individually, as We or Us.” But these small things add up to big things, to questions about life and love and why things are the way they are. As Roy herself puts it: “Little events, ordinary things, smashed and reconstituted. Imbued with new meaning. Suddenly they become the bleached bones of a story.”

Read The God of Small Things here.

About the Author: Arundhati Roy

Arundhati Roy, the renowned author of “The God of Small Things”

Arundhati Roy is an Indian writer and political activist. She won the Booker Prize in 1997 for her novel, The God of Small Things, and has also written two screenplays and several collections of essays. For her work as an activist, she received the Cultural Freedom Prize, awarded by the Lannan Foundation in 2002. Her latest novel, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, was released on June 6, 2017.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.