“Screenwriting is not the glamorous profession it’s made out to be”, explains award-winning, professional film and television scriptwriter Clive Dawson in this candid interview. “It’s a hard slog, with few rewards and a great deal of heartache. However, the enjoyment is to be found in the process, not the end result, and just occasionally, it’s worth the effort.”

Who is Clive Dawson?

Clive Dawson has been a professional screenwriter for over twenty years, writing extensively for UK television and contributing to several top-rated ITV and BBC dramas, including THE BILL, CASUALTY and HOLBY CITY.

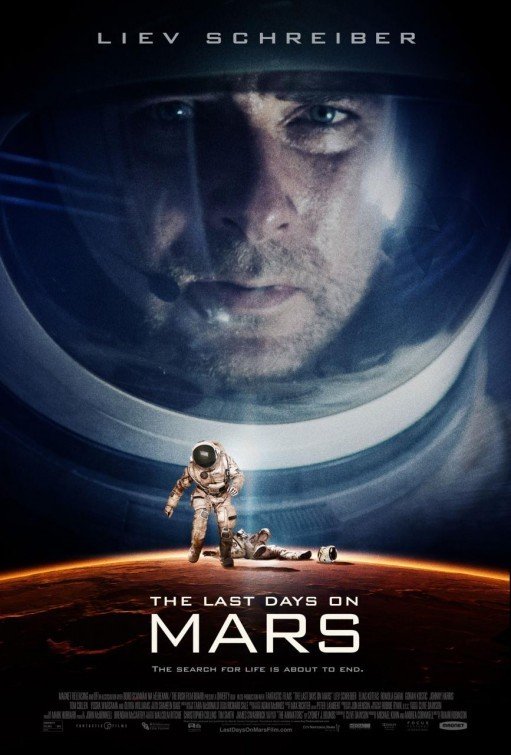

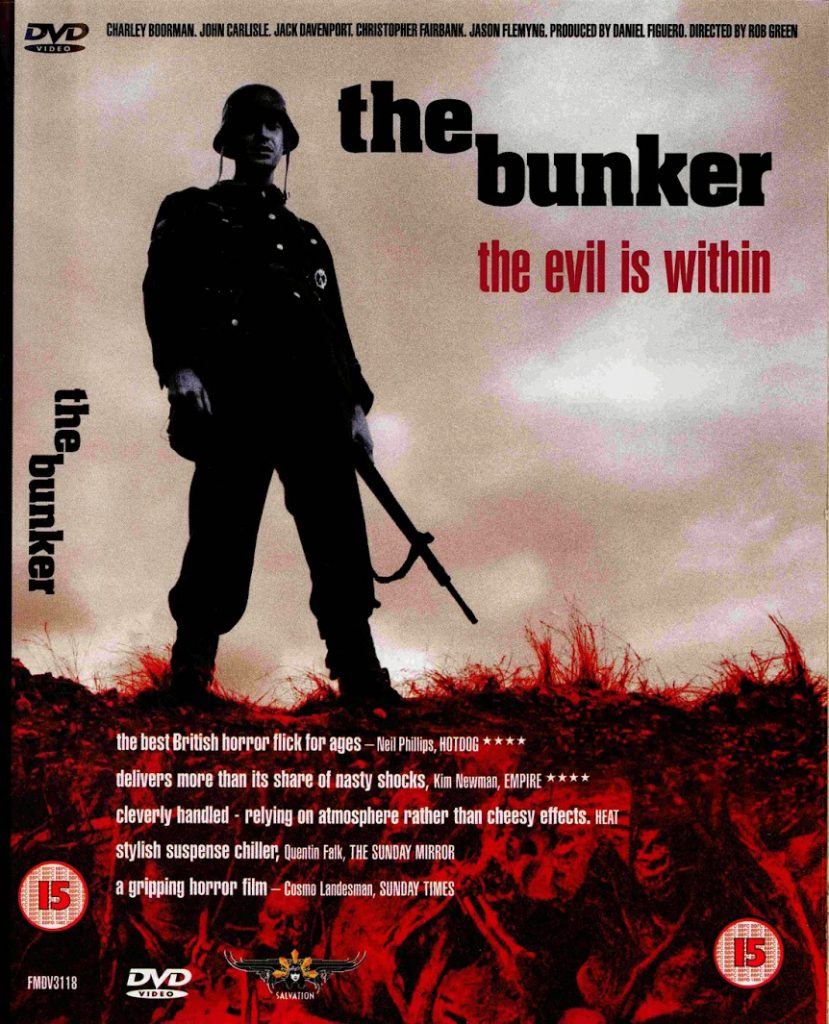

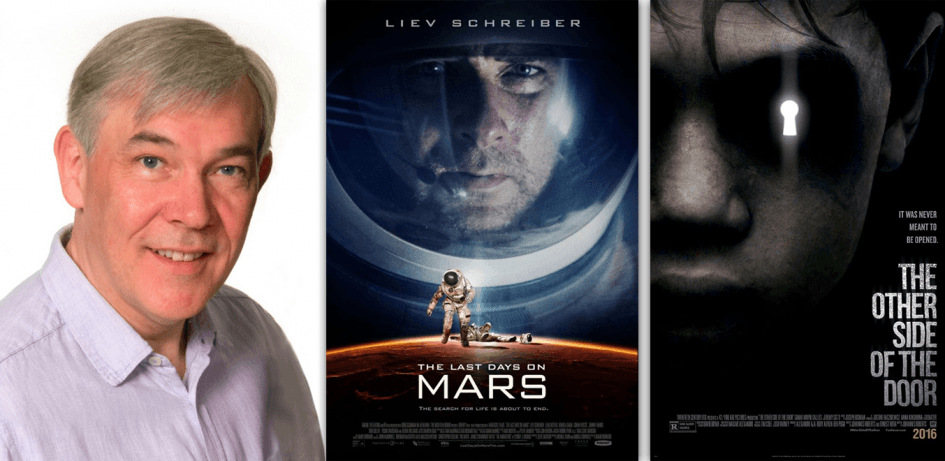

He wrote the original screenplay for the wartime-based supernatural thriller THE BUNKER (2001) and was the screenwriter and associate producer on the sci-fi thriller THE LAST DAYS ON MARS (2013).

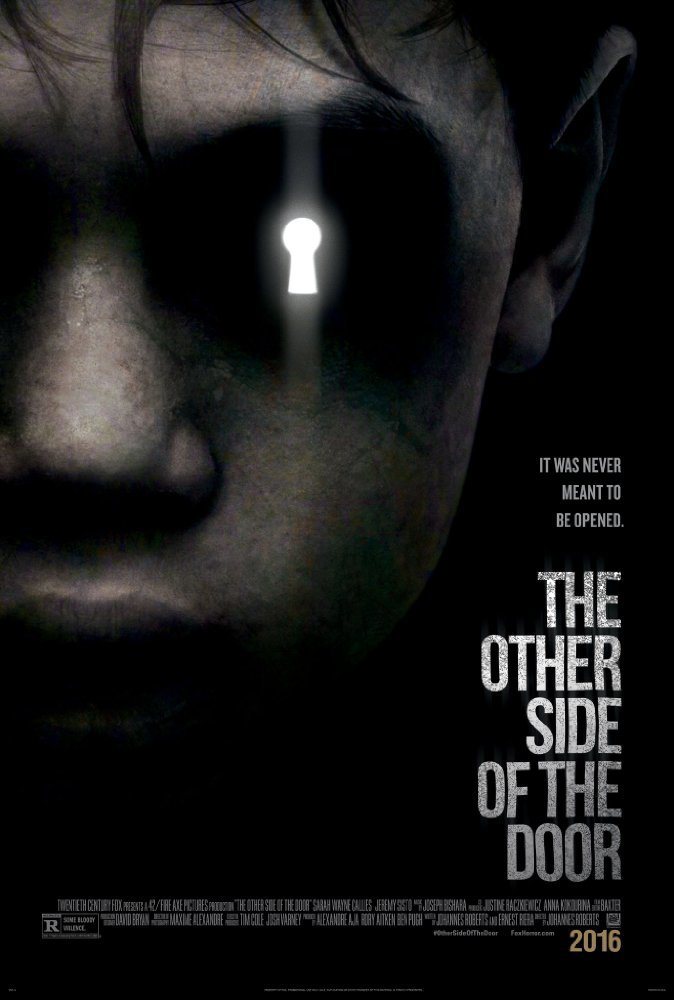

Since then, he’s worked on several projects for Fox International Pictures, including uncredited production rewrites on the recently released supernatural thriller THE OTHER SIDE OF THE DOOR (2016).

Currently, Dawson is writing THE ABOMINABLE SNOWMAN for Hammer Films, a re-boot of Hammer’s classic 1957 thriller which starred Peter Cushing, and also adapting Bob Leman’s Nebula award-winning sci-fi short story, WINDOW.

The sci-fi thriller THE RUUM, currently in pre-production in Australia, is based on his spec screenplay, adapted from Arthur Porges’ short story.

His adapted screenplay The Animators (filmed as Last Days on Mars) was not only voted onto the Brit List of Hottest Unproduced Screenplays in 2010, it also secured high-grade Hollywood representation.

Dawson is a member of the British Academy of Film and Television Arts, The Writers’ Guild, The Society of Authors and The Crime Writers’ Association.

He has written countless hours of television drama, plus three produced feature films, numerous unproduced scripts, and three films currently in development or pre-production.

Dawson won a Writers’ Guild award for his work on the UK cop TV show. He’s represented by 42 Management & Production in the UK and Verve Talent & Literary Agency in the US.

Visit Clive Dawson’s website or IMDB page to learn more about his work.

Enjoy reading Dawson’s screenplays “The Last Days on Mars” and “The Bunker”.

Trailer of The Last Days on Mars

Interview with Clive Dawson

Q: What genres do you mainly write in?

I specialise in thriller, suspense and science-fiction genres. I also write in the traditional horror genre, as opposed to the contemporary definition of film horror which has come to be associated with slasher and torture-porn, which I loathe.

Traditional horror is based upon atmosphere, suspense and genuine fright, rather than graphic violence.

I’ve always been fascinated by other worlds, other periods, and the darker aspects of the human psyche.

Q: What is your latest screenplay Window about?

My latest spec screenplay, which I recently finished and sold almost immediately, is based upon Bob Leman’s Nebula Award-nominated short story of the same name. It’s about a group of experimental parapsychologists who accidentally discover a gateway to an apparently idyllic alternative dimension. But all is not as it seems, and the gateway proves to be a metaphorical Venus fly-trap.

(“Window” was first published in 1980 and has since been reprinted numerous times. The story was featured in the 1981 Annual World’s Best SF Anthology.)

Q: What made you adapt Leman’s story into a screenplay?

I first read Bob Leman’s short story three years ago, and I immediately knew I had to find out if the film and TV rights were available for purchase. I knew I wanted to adapt the story into a feature film, as I had done with previous literary properties I’d discovered and optioned.

Q: How long did it take to adapt Window into a screenplay?

The script was written over a twelve month period.

Q: What was the hardest part of writing Window?

The short story has a wonderful twist ending, but the narrative didn’t sustain for the necessary ninety-minutes of screen time.

I had to bring a whole new dimension to the story, expanding it in various ways, as well as devising new characters and relationships for the protagonists.

Q: At what age did you start writing?

I began writing at the age of eight or nine.

Ever since I was a child I’ve wanted to be a writer – though why, exactly, I cannot say.

If I could have my time over again I’d become a novelist instead of a screenwriter.

The screenwriter, especially in film, has little or no control over the end result that appears on the screen, despite being the primary architect of the movie.

Q: What were your first stories about?

My first stories were based on television programmes I’d seen, or comic-strip stories I’d read. My tales were hugely derivative, but I learned much about story structure during the process.

Q: How did you launch your screenwriting career?

I launched my career simply by writing scripts on spec and sending them out to producers, script editors and agents.

Eventually, I landed an agent, followed soon after by my first commission to write for a long-running cop show.

Since then I’ve written countless hours of television drama, plus three produced feature films, numerous unproduced scripts, and three films currently in development or pre-production.

Q: What was the biggest hurdle you’ve had to overcome?

The biggest hurdle I’ve had to overcome is my own lack of confidence, both in my writing and in networking. I’m not a naturally outgoing person, so I’ve always allowed my writing to speak for me.

Q: What kept you going?

What kept me going was the need to earn a living! If I didn’t sell stories, I didn’t pay the mortgage.

Q: Tell us about your career as a screenwriter

I’ve been writing full-time for over twenty years. I’ve always been a freelancer; I’ve never been employed on a team of staff-writers, though I have worked within teams of other freelance writers. I love the process of creating stories, but I despise the way writers are treated in this industry. The ‘auteur theory’ has a lot to answer for.

Q: Why do you feel screenwriters are treated badly in the industry?

Screenwriters are considered an expendable asset in the industry. Under the old Hollywood studio system, writers had to follow the dictates of the producers, as did the directors (on the whole) in those days. With the collapse of the studio system and the rise of the ‘auteur’ theory, writers now have to follow the dictates of not only the producers, but also, primarily, the directors.

Directors have become all-powerful.

Occasionally, a good, strong producer will defend the work of the screenwriter against the interference of the director, but those instances are rare. Even when a writer has created the entire project from scratch by writing an original screenplay, the director has final say and will impose whatever changes he or she sees fit, regardless of whether or not it harms the writer’s property.

As you can see, I’m not a supporter of the ‘auteur’ theory, and if they’re honest, I’m sure most screenwriters would agree. Filmmaking should ideally be a collaborative process between writer, producer and director, but in reality it is one ego imposing his or her will over all the rest.

This is particularly hard to bear from a director with little or no experience, directing their first feature but behaving as if they know everything there is to know.

This isn’t to say that screenwriting is a completely hellish experience.

I’ve worked with many, many talented producers, directors and executives over the years, and some of the most rewarding experiences of my life have resulted from developing feature scripts to a point at which financiers buy into the project and say, yes, this is worthy of spending millions of dollars to make.

Q: What is the hardest part of being a screenwriter?

The hardest part of being a screenwriter is watching changes being imposed on a piece of writing that you know in your heart will undermine the narrative, yet are powerless to stop it.

Q: What heartaches have you encountered?

I’ve been re-written behind my back, I’ve had directors claiming that they wrote scripts that I’d written, I’ve had producers circulating my script with all traces of my name removed, and I’ve had changes imposed on scripts that have literally destroyed the property.

Q: Have you ever had a script ripped off?

Yes, I once sent an original screenplay to a production company who were clearly excited by it. However, they passed on it. A year or two later, when my script was in production, we learned that an almost identical story was also in production, being made by the company who’d passed on my script in the first place.

Fortunately, ours made it into release before the ‘alternative’ version.

Q: Have you had to tolerate insults?

I’ve had all kinds of insults thrown at me by directors, over the years, because I’ve refused to simply take dictation from them. I’m a writer, not a typist. But the most painful insults are reviews of films in which I’ve been singled out for criticism as the writer, even though what appeared on the screen bore absolutely no resemblance to what I’d originally written.

Q: What was the nastiest experience you’ve had in the industry?

Being abused behind my back by an arrogant and spiteful director, who told a pack of lies to the producer which ultimately got me replaced on the project.

Q: What makes this career a “hard slog”?

The fact that, on every single project, you’re effectively starting from scratch. No matter what credits or experience you’ve had previously, the only thing that matters is what you put on the page this time around. No amount of ‘brownie points’ from previous work will save you from being fired or replaced if you don’t get it right this time.

But, finishing on a more positive note, there’s nothing like the satisfaction of creating a workable story from scratch, that attracts the attention of producers and financiers. The reward and fulfillment is to be found in that process in most cases, not in what finally appears on the screen.

Q: What do you consider your best accomplishments?

My best accomplishments have, sadly, been early drafts of screenplays that were subsequently mangled by inexperienced first-time directors.

Q: What was the most amazing moment of your career?

The most amazing moment of my career was being invited by the world-famous Hammer Films to write a reboot of one of their classic movies, THE ABOMINABLE SNOWMAN.

Q: Do you ever suffer writers’ block?

I don’t believe in writers block. You’re either trying to break a story, or you’re not. If you’re going through the process, no matter how hard it might be, you’re not blocked.

Q: What is your work schedule when you’re writing?

I work office hours, all week, and sometimes also at weekends if I’m facing a deadline.

Q: How did you snag your agents?

All my agents took me on in response to scripts I’d written.

Write a good, commercial script, and you’ll eventually find an agent.

Q: What is your best advice to aspiring writers?

Take courses, read books, read scripts, but most of all, write, write, write.

Write a great script and you’ll get into the industry. Without a great script, you probably won’t.

Q: What do you love doing asides from writing?

I love reading, and watching movies.

Q: Which writers do you admire?

The writer I admire most is Michael Crichton. He was a genius, in my opinion.

Q: What are your big goals and ambitions?

To write at least one good novel.

Q: What do you most love about writing?

The freedom to create.

Thank you, Clive Dawson, for taking part in our interview!

November 4, 2017 at 6:19 PM

Great interview!! Love “The Other Side of the Door”!

November 4, 2017 at 6:22 PM

That must have been really painful to have your story stolen 🙁