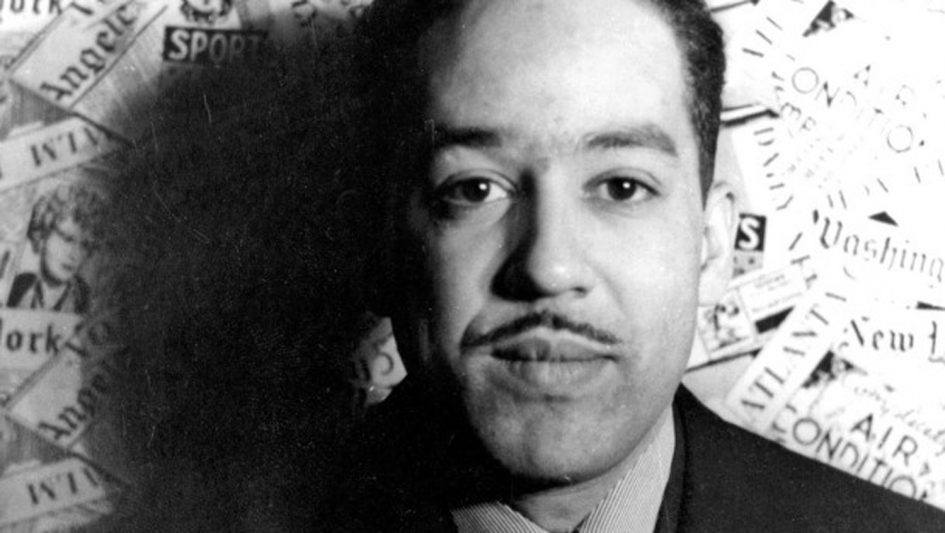

One of Langston Hughes’s admirers, Loften Mitchell, writes: “Langston set a tone, a standard of brotherhood and friendship and cooperation, for all of us to follow. You never got from him, ‘I am the Negro writer,’ but only ‘I am a Negro writer.’ He never stopped thinking about the rest of us.”

Born in February of 1902, Hughes was one of the leading forces of the Harlem Renaissance in New York City during the 1920s and continued to influence the tone of African-American poetry throughout the mid-1950s and mid-1960s. However, before his career took off, his main inspirations stemmed from his upbringing.

With his parents separated and mother traveling to seek employment, Hughes was primarily raised in Lawrence, Kansas by his maternal grandmother, Mary Patterson Langston. Passing on stories about her generation’s activist experiences, Mary Langston was undoubtedly the reason behind his unwavering sense of racial pride.

Hughes’s love for writing began in high school, beginning with him writing for his high school’s newspaper and editing the yearbook to him eventually writing his first short stories and poetry. In 1921, his first poem, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” was published in The Crisis, the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and soon became his signature poem.

Lines such as “My soul has grown deep like the rivers” resonate with Hughes’s deep-rooted connections to his African-American ancestors and past.

At the young age of only seventeen, he wrote this poem to commemorate these ancestors who have been building a life for themselves since ancient times despite the discrimination they were forced to face.

Starting from this one poem, Hughes moved on to earn the title of a “people’s poet,” depicting the real lives of the African-American community and all of its diverse culture. Rather than expressing anger and hatred, he wanted to spread the honest beauty of its multi-faceted identity and embrace the working-class blacks that many tried so hard to disparage.

From the late 1920s to the mid-1950s, he continued to write poetry, novels, short stories, plays, and works for children, and even won the Harmon Gold Medal for literature in 1930 for his first novel, Not Without Laughter. However, as the mid-1960s approached and the subject matter he was writing about became less relevant in light of more racial integration, many younger generation black writers considered his work to be outdated and too racially chauvinistic.

On the other hand, Hughes thought the exact opposite, finding many new writers to harbor too much anger and vulgarity in their writing. They lacked the racial pride he worked so hard to maintain.

Hughes’s main goal in his writing was to uplift the black community and inspire young black writers to be objective about their race instead of being ashamed or detach themselves from it. He wanted to open his readers’ eyes to the social conditions around them and not circumvent or fall into the stereotypes people influenced others to perpetuate.

He set aside hate to stress the importance of racial consciousness and unity.

Mitchell was right. Anyone could have written about the black community, about the racial stereotypes that prevailed during his time period, but Langston Hughes did so in a way that lifted everyone up and kept people thinking about each other.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.